Collective learning – the scientific method

Knowledge can be gained through Intuition, Authority, rationalism, Empiricism (observation, experience, experiment) and the scientific method which can make use of all of the above.

By this means, the collective knowledge of humanity itself increases through the generations, more accurate and far ranging models come to exist. We find out more about the expanses of space, about the nature of sub-atomic particles, about the way our brains work.

One thing is certain, there is always more to find out. We cannot see the limits of existence. Indeed, we cannot even see the limits of the physical Universe. There never can be a Theory of Everything which is able to explain everything that there is, both seen and unseen. To believe otherwise is to place humanity in the place of God and is totally unrealistic.

Since at least the 17th century, the process of observing the world around us and making models has often been formalised in what is called the “scientific method”. While this method developed out of common sense knowledge grown out of the practical concerns of everyday living, it is more than just organised common sense [Nagal 1961] . It aims at providing an explanation of what is observed rather than just noting cause and effect. In addition, steps are taken to establish the correctness of the conclusions drawn and to mitigate the biases which exist in the minds of the investigators.

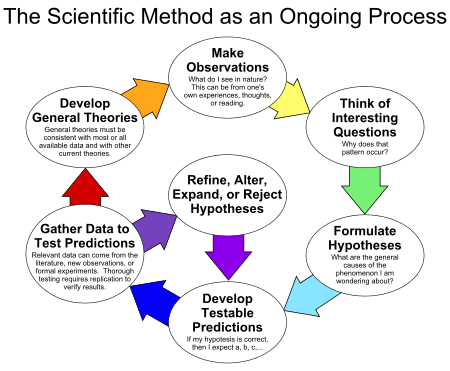

Applying the scientific method to a question entails a number of steps, illustrated in .

- Careful observations are made

- Interesting questions about the observations are formulated. eg. “Why does this happen?”

- Suggest a possible explanation, or hypothesis, or model, which can be based on intuition, analogy, guesswork or anything else.

- Make testable predictions using this hypothesis and do experiments to see if these predictions are accurate.

- If not accurate then refine the hypothesis or jump to a new one and go back to step 4.

- If accurate then incorporate them into general theories.

In addition to this, it is important that the observations and reasoning of an experimenter, or team of experimenters, is rigorously checked by others who are not involved. This is to minimise the effect of “confirmation bias” in which a person is likely to give undue weight to an observation which confirms what they believe for other, possible irrational or erroneous, reasons and to discount, or not even notice, observations which are contrary. For this reason experiments should ideally be repeatable. Clearly if the field of investigation is large, such as in astrophysics or the origin of life, that is not possible so other cross-checks need to be introduced.

The goal of a scientific investigation includes describing, predicting and explaining particular observations. They can also enable allow the thing which is observed to be influenced in ways which the scientist wishes. A scientific hypothesis can provide a simplified or unified description of apparently disparate phenomena. A scientific investigation should also creates public knowledge. Knowledge which can be shared and checked by means of the publication of results.

Just as in individual children who become adults, as a society we develop and learn. The accepted and taught models of the external world become more sophisticated and accurate. Old ideas, and old predictive equipment is replaced by new. Sometimes the new is a direct development of the old.

Examples are the Laws of Motion and the Law of Gravitation which were expressed in a simple form by Newton and which were shown by measurement to correctly predict the motion of the planets in the solar system as well as the trajectory of a projectile on Earth. Later, when more measurements, and more precise ones, were made, it was found that Newton’s Laws were not completely accurate. When Einstein formulated the Theory of Relativity, itself a response to observations in electromagnetism, it was shown that gave more accurate predictions to which Newton’s laws were an approximation.

Sometimes the old has to be totally discarded because new information, or new situations, have come to light for which the old gives totally the wrong answer. There is a change of paradigm [Kuhn 1962]. The Copernican idea that the Earth was the centre of the Universe had to be replaced with the quite distinct ideas of Galileo in order to make sense of the information provided by the new telescopes. The only test of the validity of the mental models formed is whether predictions agree with experience. Although a model can, in principle, be proved false in that it gives false predictions, the fact that a model gives the correct result is no indication of it’s closeness to reality. The Copernican model gave very good agreement for a long time but it was found to be false.

In contrast to this, the change from Newtonian mechanics to relativistic mechanics required only that the existing hypothesis be refined and extended to increase accuracy. The old was an approximation, valid under special conditions, to the new.

On the smaller scale, we form models for the behaviour of things in our world. That chairs can be sat on without collapsing, that fire hurts if we get too close, that if we do certain complicated things with magic wands or computer keyboards then we can make things happen. This doesn’t mean that our model is true, just that it works in the situations in which we have tested it. Of one thing we can be sure, however, is that no matter how sophisticated and accurate our models are, they will be incomplete.

The essence of exploration, whether scientific or geographical, is based on the experience that there are always new things, new places, new experiences to be found. Not even on this Earth, or even in this land, will anyone be able to say: “We know everything there is to know about this”. How much less about the whole Universe?

This approach has been hugely successful in constructing a model of the Universe which describes how observations in Physics, Chemistry, Biology can have come about. Moreover, many predictions based on the hypotheses have been and shown to be correct.

What do we do if an observation disagrees with a hypothesis?

If an experiment is carried out and the result disagrees with that predicted by the prevailing hypothesis, there can be several reasons.

- The hypothetical model is fundamentally wrong, eg. Earth-centred Universe.

- The model is approximate and can be extended to improve the accuracy in the new situation. The old is an approximation to the new. eg. Special relativity.

- The experimental conditions are not fully, or incorrectly known. In which case the hypothesis can be correct and will give agreement if all the surrounding conditions are specified. eg. Uranus.

According to Logical Empiricism, as expressed by Popper, a single disagreement between prediction and observation is enough to throw out the hypothesis. This would have caused Newton’s mechanics to be discarded in situation (3) above which would have been clearly inappropriate. Investigating the reason for the discrepancy to see where it arises is what is generally done.

If a succession of experiments give results which disagree with hypothesis then the pressure to seek a new hypothesis grows. It becomes apparently less likely that it is the experiments which are lacking as the hypothesis is either incomplete or wrong. For a number of reasons, some good and some bad, the pressure has to mount to a certain level before the prevailing hypothesis is abandoned. When that happens, there is a rapid shift to a new, and possibly very different, hypothesis which give more accurate agreement and has the virtue of parsimony